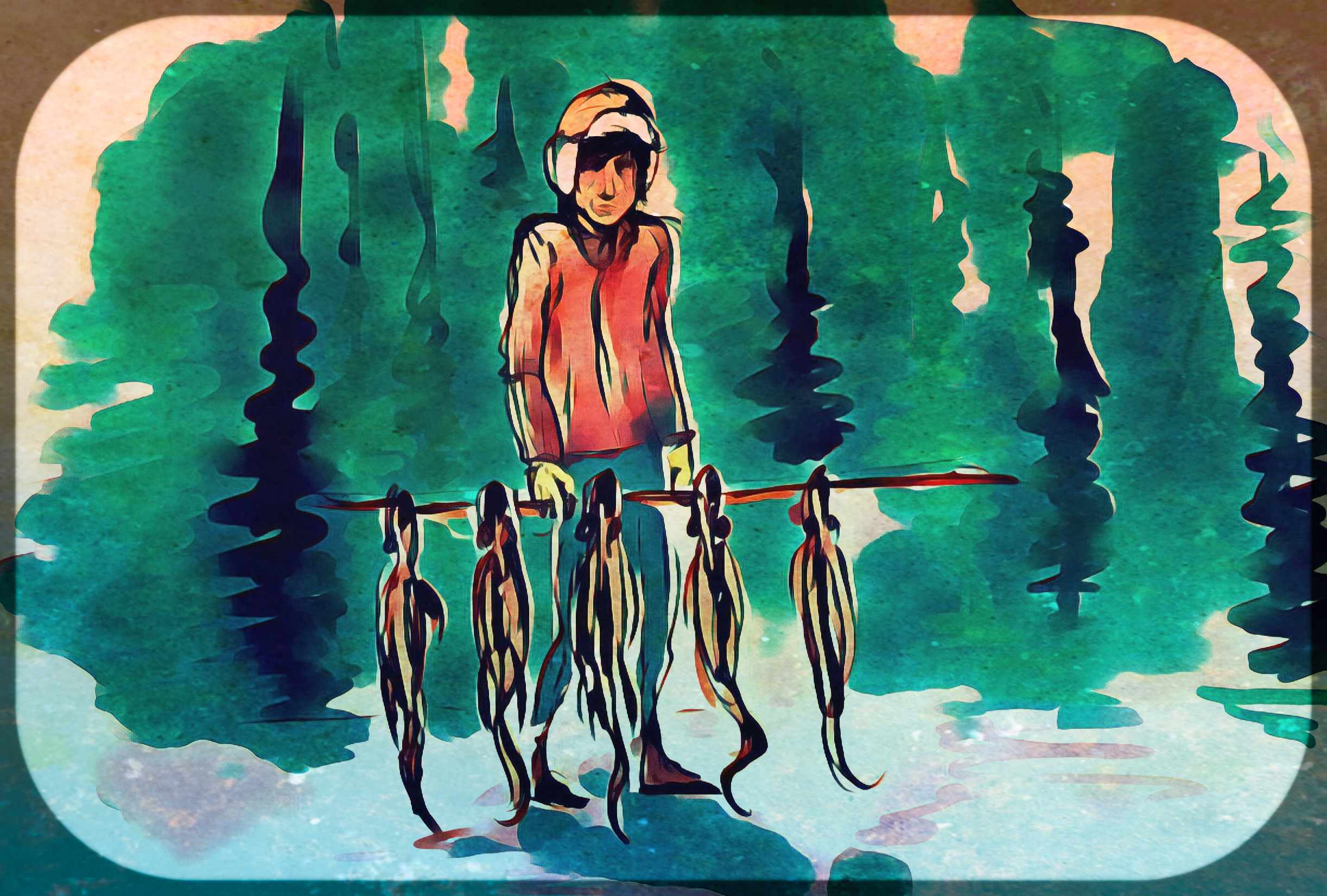

Edward Cardinal was born in 1938, the first of three sons for Jim Cardinal and his wife Delphine Bourque. He and his brothers spent a lot of their early years with their dad on the trapline. As Edward describes it, the family hunted “just about everything,” including prairie chickens, deer, moose, caribou and ducks: “We had dogs, you know, that’ll chase the ducks into the weeds.” The dogs would “spook [the ducks] or else, if they were in a grassy area, they’d catch them themselves.”

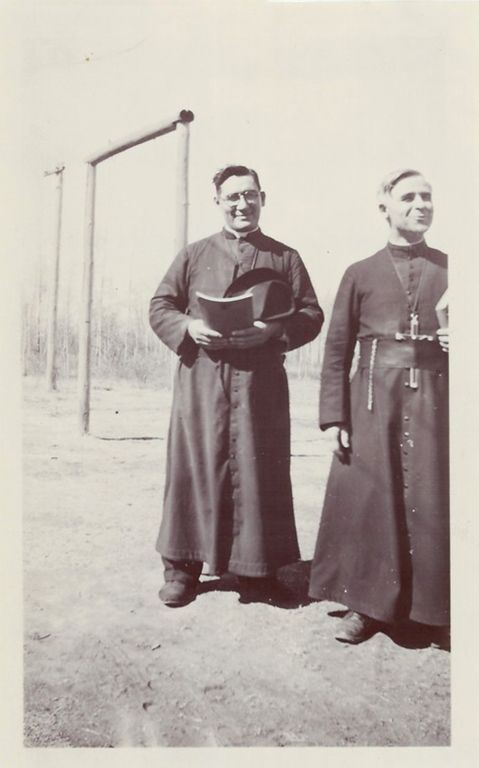

As a result of the School Truancy Act — a law mandating children to attend school — Edward and his brothers were forced to leave the trapline. This was encouraged by their father: “He wanted us to go to school, I guess they were right on their part about that.” Going to school in Philomena, AB (north of Lac La Biche), Edward was taught by Father Mercredi.

Recalling his time there, Edward said there were certain aspects that he enjoyed; however, “like any other school I guess, there’s parts that I wouldn’t have nothing to do with it. It was a lot of religion, you know, mostly….” What Edward really loved was being out on the land, hunting and trapping.

As well as learning academic foundation at school, and about the Bible, Edward also encountered his first love at Philomena. He and Virginia Bourque would marry in Philomena in 1954; the officiant at their wedding was the same Father Mercredi that had taught Edward as a boy. The couple would go on to have four children and nine grandchildren.

Upon completion of school, Edward began working for the railway: “in ’55 at 80 some odd cents an hour and you worked hard for your money on the railroad,” he said. “Everything is heavy except the shovel, the rest of the stuff is backbreaking, you know, making ties, big spikes you had to drive the—the only thing that was light was the shovel.”

Since railway work was seasonal, Edward would spend the winter on the trapline procuring furs for extra income.

Like his own parents had, Edward and Virgina decided to move off of the winter trapline so their children could attend school. It was then that Edward quit working for the railway and got a job in the oil and gas sector. At first, he found work for only five dollars an hour. Once he landed a union job his wages went up to seven dollars an hour.

While the money was good the work had a downside which was that Edward was not able to go into the bush to hunt and trap like he had in the past. For Edward, this was a profound change. He could trap on the weekend or after his work shifts, but that was time really meant for spending with his family. The change was hard for someone who had grown up with trapping, and who had spent “every free day out in the bush”. After retiring as a heavy equipment operator in 1993, Edward was finally able to spend more time at trapping.

As Edward is now older, he says he is less able to get out on the land. Thankfully though, Edward’s son joins him out on the trapline: “He’s been my junior partner for the last three or four years now, because I haven’t been able to walk in the muskeg or anything like that…” Edward realizes that he won’t be able to spend as much time on the trapline in the future, but his hope is that the trapping tradition will continue: “I want to transfer the line to my son and my brother, so it’ll stay in the family,…”