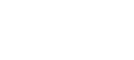

In the far reaches of northeastern Alberta, on the western tip of Lake Athabasca, is Fort Chipewyan, or Fort Chip as it is fondly known by locals. As a hamlet, Fort Chip falls within the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, half way between Fort McMurray and the NWT border. Fort Chip is 593 km north of Edmonton, AB.

Roderick McKenzie of the Northwest Company established Fort Chipewyan in 1788 as a fur trading post – named for the Dene Tha’ people of that area. The location of the fort was chosen for its accessibility by canoe or York boat in the summer, and by dog sled in winter.

The mid-20th C brought winter roads that connected Fort Chip to Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories, and to Fort McMurray in the south. Winter roads are only functional when there is enough snow and ice to support the weight of large vehicles. Once the ice has broken on the rivers in the spring, Fort Chip can also be reached by air (since 1966). For more adventurous types, access is also available via the Athabasca River from the south. The latter tends to be undertaken for recreational or symbolic purposes these days.

In addition to complex transportation in the region, those living in Fort Chip long did so without electricity. The first house in the hamlet to get access to electricity was in 1959, and the first telephones arrived shortly thereafter, in 1962.

Despite these seemingly insurmountable challenges, the Dene, Cree, and Métis peoples living in Fort Chip over multiple generations have a long history of thriving in the area. At their core, their stories also teach about the importance of family and community. One such story in particular offers a remarkable example of personal ingenuity and resilience and the strength of a resilient and cohesive community.

Violet Hansen was born in Fort Chipewyan in August of 1927. As the eldest of nine children born to Jenny and Edward Flett, Violet’s life history offers intriguing insights into a uniquely Métis way of life in Fort Chip in the early decades of the 20th C. As Violet describes it, hunting, fishing, and gathering were activities that ensured the family’s survival. Ducks, geese, ptarmigan and muskrat were common food sources. The way she tells it, “there’s nothing to setting rabbit snares.” Rabbit was consumed often by the family.

Accompanying her dad on a hunting trip one day, Violet asked him what they were going to be eating later that day. Her dad’s response was, “ptarmigan”. They caught about six low-flying ptarmigan in all, “So that was good for a couple of days, next day we’d get some more.”

Fishing was also an important food source for the Métis community in Fort Chipewyan. Because of the community’s location beside Lake Athabasca, whitefish, jackfish, and pickerel were all plentiful. Berries were picked by family groupings in late summer, but as Violet explains, care needed to be taken given that other species, i.e. bears, also favoured the berries at this time of year.

With no electricity at home while growing up, Violet says that food had to be prepared in such a way as to ensure that it wouldn’t spoil. Canning and making dry meat were customary practices: “no deep freeze or anything, (we) hung our meat and everything in the fall. Spring, we’d can our meat, or bottle, whatever.”

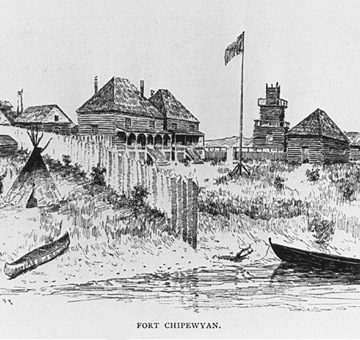

Violet recalls the family using a coal oil lamp as well as candles to light their home. Heating relied on ensuring sufficient supplies of firewood for the long winter months. As for ironing and washing, families would use a “gas iron to iron your clothes,” and the washing machine had to be activated by hand. By today’s standards, living in Fort Chip during Violet’s early life would have required lot of hard work!

Since the family didn’t have a vehicle when Violet was young, they relied on dog teams for transportation. The dogs were also important for completing chores around the house. Violet was responsible for doing a lot of this work, “I was the tomboy because Dad wasn’t making that much when he was working for [Wood Buffalo National] Park and he had to go out there and—three kids sick at home, who’s going to do the work? I did. That’s why I had my own dogs. Go in the bush and cut my wood, haul it in.” Since her family also didn’t have running water, Violet was responsible for hauling water from Lake Athabasca: you would fill a forty-five-gallon drum, put it on your dog sleigh, “put snow, freeze snow on the top, so the water wouldn’t splash that much and bring it home.”

Violet’s story reflects a profound sense of self-reliance and shared responsibilities. Everyone in the family would pull together to get things done, and everyone was always ready to help everyone else. This ethos was also prevalent in the broader Métis community, for example in the way that families shared with each other following hunting and fishing trips.

When neighbours and relatives came calling, Violet explains that often times this was for medical purposes. In particular, folks would come to see Violet’s mother, Jenny Flett. Jenny was born in Fort Chip in 1905 and later would become quite famous for the life giving work she performed for so many.

Growing up, Jenny’s own mother had been chronically ill which meant that Jenny had to assume responsibility for the care of her younger brothers and sisters. At sixteen years of age, Jenny’s mother passed away. For two years afterwards, Jenny was the primary caregiver for her siblings. When she turned eighteen, she recalled thinking, “I’m going to do something with my life. I don’t know what made me think that, you know, because mom used to be a midwife and I thought to myself, that would be a nice job, there’s no doctors, no nurses there. Then I fell in love of course, and I had to go and get married, which didn’t stop me. It’s a good thing my husband let me do as I like. So I went to Edmonton, bought myself a doctor book of maternity, and I said, I want a good book that I can go by because I’ve got no education. You see, I only went to school four years because mom was sick all the time.”

A mail order doctor’s medical manual, Jenny’s childhood memories of being present at birthings her mother had delivered, and the experience of having her own children informed Jenny’s early practice ot midwifery. Jenny admitted later that she had not seen many deliveries that her mother had performed, “she wouldn’t let me go where the baby was born. I could hear the mother moaning and crying and I thought, ‘I wonder what my mom’s doing with her?’ I was in the other room but she wouldn’t let me go, she said I was too young to see things.”

In 1928, at the age of twenty-three, Jenny delivered her first baby as a midwife. Recalling the event 79 years later, when she was 100 years old (in 2007), she said “Yes, I remember it all right. I only had one of my own. And we were out on the Athabasca Lake there, in the fall of the year, fishing you see. My husband was fishing for the dogs for the winter. And one night, oh was it ever rainy and snowy and dark you know, in the fall of the year and a knock at my tent door. The man standing there says, “Mrs. Flett.” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Do you know anything about maternity?” I said, “I’m just going to try and get to maternity. I wrote out for a book for myself.” He said, “My wife’s in labour. Do you think you could come and help me?” I said, “Sure.” And that was my first one. …I wasn’t scared because I was reading my book already you see.”

That baby was the first of hundreds of babies that Jenny Flett would deliver before she retired at the age of 75. In the 50 years she practiced as a midwife, Jenny delivered 487 children without losing one of them, or any mothers either. Jenny was well-known in the Fort Chip community for her skill and care during deliveries, which included massaging the mothers and administering home remedies to aid in the recovery process. Jenny saw midwifery as her duty and thus did not charge the family for her services. Unlike her own mother, Jenny made sure to bring her daughter along whenever a baby was on its way, “she always had me with her,…I was still young,…I used to go with Mum all the time, I’d help her out,” she said. In part owing to changing times and greater access to medical services, Violet did not become a midwife like her mother.

In addition to the chores she had as a youth, Violet has fond memories of seasonal trips to Wood Buffalo National Park, “I used to go trapping with my brother Sonny for seven years in the spring of the year, in the park, he had his own [trap] line. Two of us in the bush for three weeks.” For the most part, smaller animals were caught, since buffalo hunting was regulated by the federal government.

In her 20’s, Violet decided to leave her home community to find paid work. She and her sister headed south, to Edmonton, where they worked as domestic help for a family. Being the self-reliant women that they were, this job didn’t last too long, “[We] got fed up with them, they were too bossy, so we quit.”

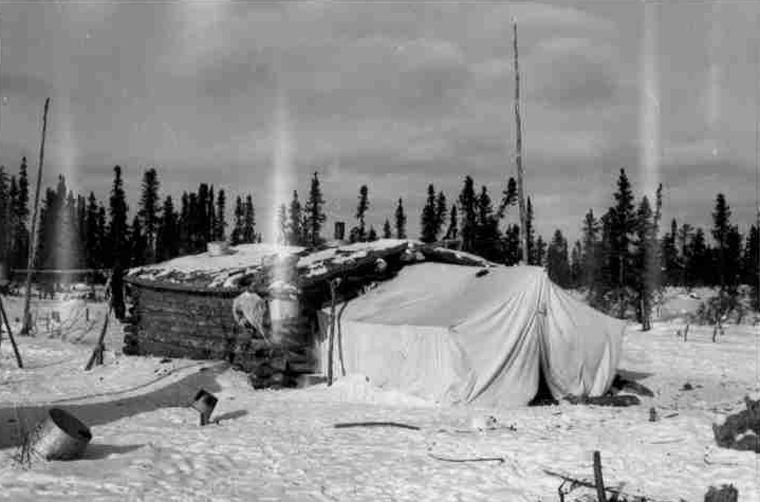

In 1957, Violet married her husband Lloyd Hansen and they spent their first year of marriage living out on the trap line in Fort Chip. The next year, the couple packed up all of their belongings and boarded a bush plane for Fort McMurray. Violet’s husband was working for Northern Transportation, a chartered boats company that hauled passengers and freight from Fort McMurray to Fort Chip and other locations within the Athabasca River watershed.

Though the move meant that Violet was away from her parents, she kept up the Métis traditions she had learned when she was younger. Snaring rabbits, picking blueberries and low bush cranberries, and harvesting her own vegetables were activities she continued to do in the Fort McMurray area. Socializing was also important and Violet often did these activities with other Métis people in the area. The meat that Violet didn’t catch herself, other community members, and later on her sons, would provide for her. Violet also managed to maintain connections with her family in Fort Chip over the years, periodically taking a trip home on a Northern Transportation boat, a journey that would last “four hours, five hours, going downstream.”

In their twentieth year of marriage, Lloyd, Violet’s husband, died unexpectedly in a “car accident, coming in from Edmonton.” Suddenly widowed, Violet continued living in Fort McMurray, close to three of her six children. In later years, the family grew in Fort McMurray with the addition of several grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Violet’s strong presence in the community is deeply respected. At 86, she remained active, including attending “bingo every night and regularly close[d] up the Legion,” all the while socializing with friends and family. Violet was named the Métis Local 1935 Elder of the Year award in 2013, and was given a Regional Aboriginal Recognition Awards Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017.