The emergence of Métis peoples are key to Canada’s pre-history. ‘Half-breeds’ as they were known at the time held important roles in the early fur trade era, serving as key economic actors including in what is today the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo. Notwithstanding the lack of a protected land base in the form of a Métis Settlement, the vibrant Métis community that emerged in NE Alberta continues to thrive today.

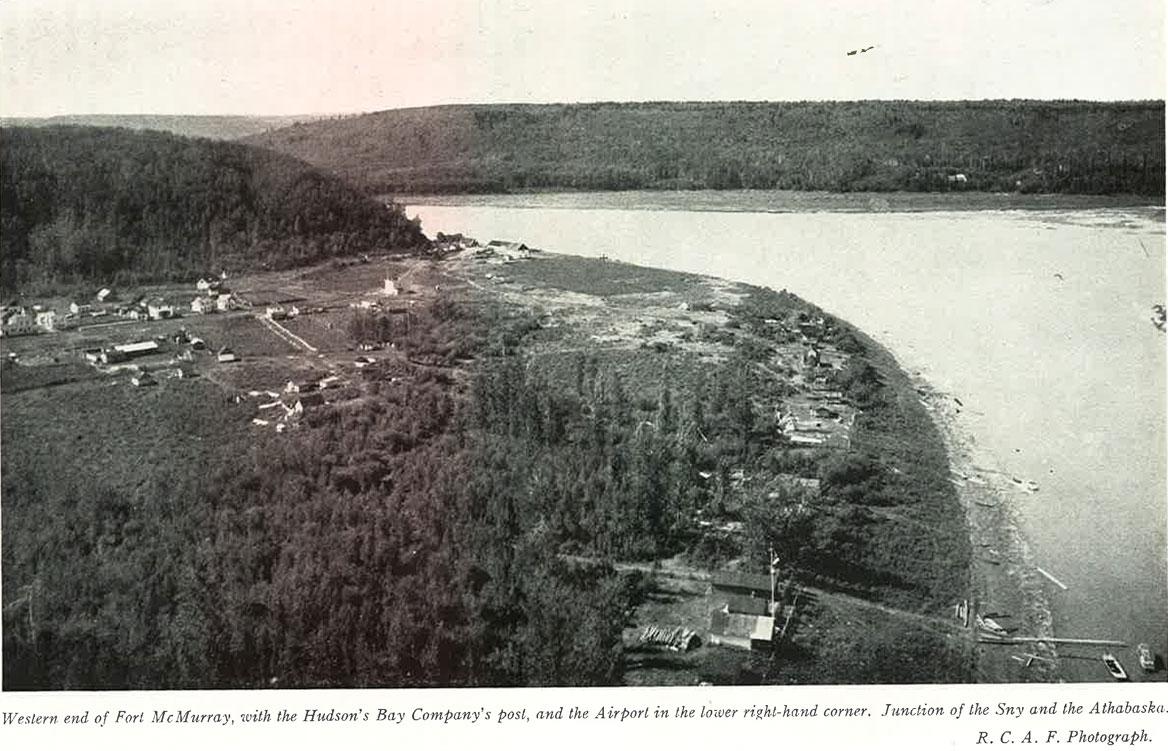

Born eight years apart, Métis siblings Lila Thompson and Roderick (Rod) Bird recall their experiences growing up in the Fort McMurray area in the mid 20th C. Lila was the fourth of twelve children born to Captain William James Bird and his wife Ethyl Fraser. Born in September 1938, she was the first child delivered at Saint Gabriel’s Hospital in Fort McMurray and the first baby baptized at St. Aidan’s Anglican Church in Waterways.

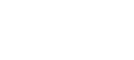

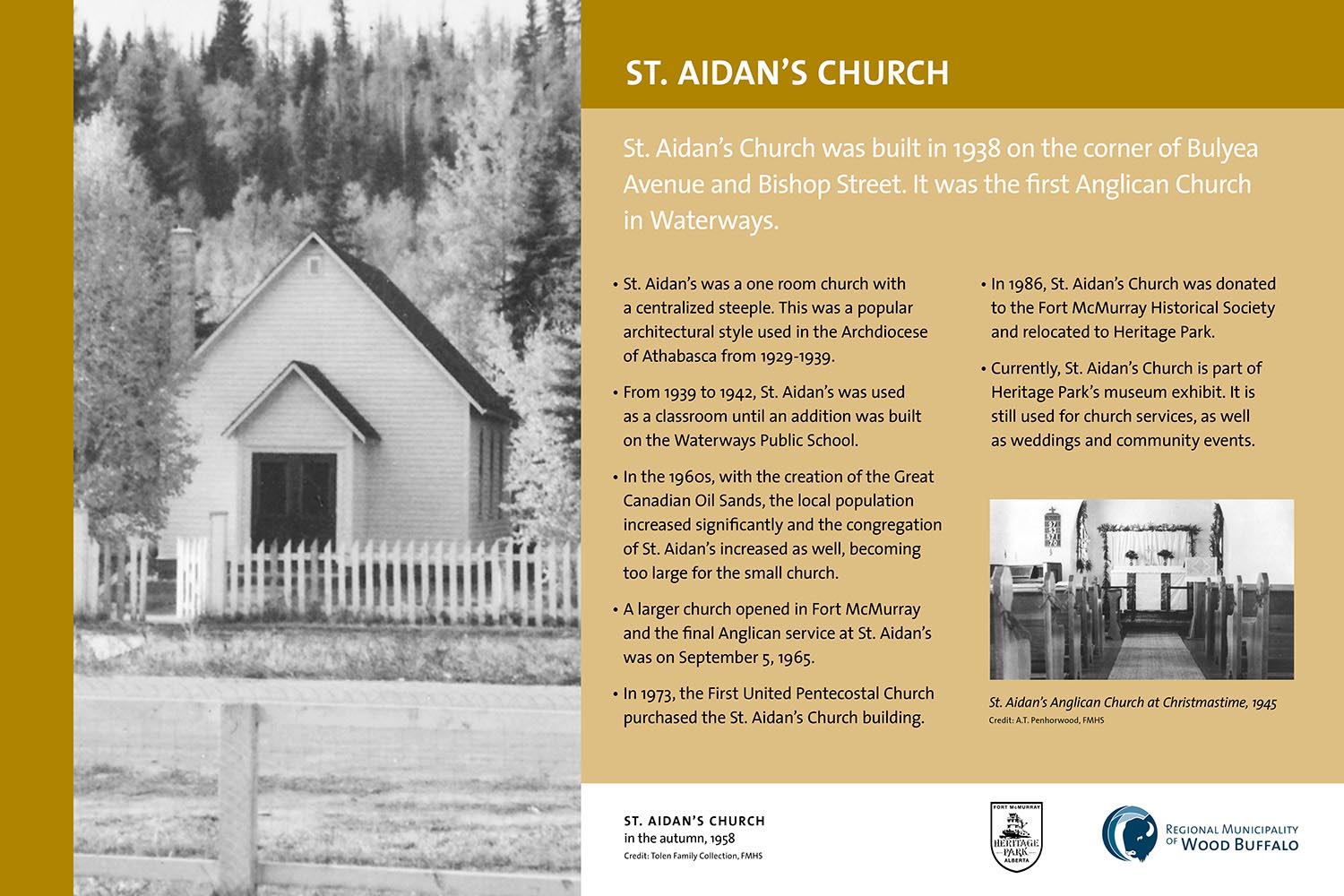

Lila’s brother Rod, born in 1946, was William and Ethyl’s seventh child. The young parents were hardworking and thus became proficient at many different things. In her younger days, Ethyl worked at the salt plant in Waterways as a way to earn extra money for her large family. William had begun his working life on the boats that transported goods and people to and from the region, beginning as a caretaker and eventually working his way up to Captain.

As a small boy, Rod and his brother were able to spend time on the boats with their dad: “We used to take turns as boys, out on summer holiday, that was our holiday…” During these times, Rod’s dad would tell stories from the wheel house that stayed with him many years later. Reflecting on these summers, Rod says, “it was just a fun trip when we were kids…I mean, we could just about get anything you wanted on the boat, as far as food, and we figured that was a real treat. You know, apples, any kind of apples, and oranges, and juices.”

But Lila and Rod’s early years brought sadness as well. Tuberculosis rates in Alberta were very high during the 1940’s and 50’s. Four of William’s and Ethyl’s children contracted TB and were sent to the Charles Camsell Hospital in Edmonton. Rod recalls that two of his sisters were hospitalized for a couple of years, and that two younger brothers were institutionalized for about a year.

The Birds could scarcely afford the long trip by train to Edmonton meaning their children mostly had to convalesce alone at the sanatorium. “It was pretty hard on everybody, really,” Rod recalls. Thankfully, Rod says that his mom was able to occasionally make a trip from Fort McMurray down to Edmonton.

Trapping was an economically and culturally important activity for the Bird family. The family focused on harvesting fox, wolf, wolverine, lynx, and beaver, and “muskrats more than anything else,” because, according to Lila, they were worth quite a bit of money at the time. With respect to food sources, Lila indicates that, “the majority of our meat came from…what Dad could catch”. This included moose, deer, caribou, and rabbit. Both Lila and Rod were responsible for providing for the family as well, with Rod hunting for rabbits and moose alongside his dad, and Lila responsible for harvesting prairie chickens. Both children also fished, with Lila focused on walleye and pike on the Clearwater River, and Rod pursuing jackfish on the Clearwater and Snye Rivers.

Lila also describes baking bread as an important activity while growing up, saying that she learned this skill from her mother: “I started baking bread, doing the kneading of the bread when I was ten years old…after a while, I just used to do the whole thing and that was my job every Saturday morning. I’d make about twelve loaves of bread, plus I don’t know how many dozen buns… like I can make really good bread, but I don’t really like to do it because I’ve—I was sick of it. I had my fill of it, you know… So yeah, everybody says, “Well, Lila, you make such [good] bread and you never—hardly ever make it.” I said, “Yeah, well, because I used to have to do it all the time and it’s no fun for me now.”

Lila says that Waterways was a small community which affected the size of schooling available to families, “I went from grade one to grade nine in the one room school in Waterways and would have had to go to Fort McMurray to Peter Pond High School”. The high school was also quite small, with “one classroom for grades ten, eleven and twelve….” Lila was one of two students in the tenth grade but soon her classmate left and she was the only one. She was also the only eleventh grade student the following year. For her final year of high school, the family decided to move to Edmonton.

Lila describes early days in Edmonton as a culture shock: “The first day I went to Victoria Composite High School, I got lost going from one classroom to the next. Like, you know, I—and I stopped and asked somebody, you know, ‘How do you get to class so and so?’ And they just laughed at me.” After two months, Lila had reached her breaking point. After a run-in with the English teacher “something snapped in me and I just picked up my books and I went to the door and I said, ‘As far as I’m concerned, you can shove this school and everybody up you know where.’ In those days you didn’t tell her exactly what to do with it, but—then I went down to the principal’s office and I said, ‘I quit.’”

Upon leaving the school, Lila happened to notice an Air Force recruiting office so she decided to go in and enroll. Lila explains that she had faced explicit racism during basic training but despite this challenge, she continued. After a short stint in Trenton, Ontario for further training, she was transferred to Namao, AB. It was there that she met her husband Hank Thompson, whom she would marry in December, 1957. A little while later the couple relocated to Ottawa, ON, where they spent 11 years. Following that, they lived in Gimli, MB, Toronto, ON and Brampton, ON.

Rod’s life took a much different path to that of Lila’s. Upon completing grade nine, Rod went to work on the boats with his dad, recalling one unnerving situation that reflects how dangerous that work could be. On a trip where the boats were moving freight from Uranium City and Gunnar to Fort McMurray, they ended up wind-bound on Lake Athabasca for four days: “there were some people had a horse that we had to bring up on a barge and that’s the same time we were wind-bound, eh. And, we had to, kind of, made a corral out of empty pallets, but the poor horse was on there for about five days, eh.” The horse lived, but “He was a little scared when he got to town here.”

Though the actual travel by boat to various destinations only took a few hours, Rod explains that work shifts could involve a few weeks at a time, “Depending where we went, a lot of times we’d just go as far as what they called The Willows, tie-up. And, if there was say, a tug coming across the lake with an empty tow, which means the empty barges, we’d take the empty barges and he’d take the full load and go back across.” He said the shifts went quickly, “on a shift we’re four [hours] on, eight off, four on, eight off. Somebody had to be on all the time.” After five summers spent working on the boats, Rod had the opportunity to become a crane operator – a job he would hold until his retirement in 2000.

Lila worked for the Air Force until 1978 at which point her daughters had gone away to college and she was beginning to die of the heavy traffic in southern Ontario. It was then that Lila, her husband Hank and their son decided to move back to Fort McMurray. After returning to the place of her youth, Lila was active in educating non-Indigenous social workers and government officials about Métis people and Métis culture in the area. Lila was so good at her job that even after she retired and her and Hank had moved to Wetaskawin, she was still getting calls to help people in the Fort McMurray area.